By: Hannah Cotton

Originally published: MenTeachPrimary

June 4th 2020

Keynote Speaker and Consultant. @HannahCaC79 #FFBInclusion

My favourite poet is a chap called Brian Bilston. His work is aesthetically and linguistically delicious – words placed on a page with such imagination and creativity, he’s a true inspiration. His infectious delight in word play encouraged me to take it up myself, reminding me how much I used to love my English lessons at school.

One example of my word play builds on equality and the role of allies. My brain child EquALLIES was born following my TEDx, #KillerStereotypes, which outlines why I think we can accelerate equality when we work together as Equal Allies. It hinges on the labels we wear, consciously and subconsciously and how we can use them to promote inclusion at home, school and the community.

Since that talk, some have called me an educator. I know my stuff and share my knowledge and experience to inform and encourage others to think differently. But it’s a label I struggle to associate with. I’m not qualified as a teacher. I’ve not got the skills and experiences you have in drawing out the potential of others. However, if listening to my conversation calls the reader or viewers to consider things differently, ‘educator’ is a label I wear with humility and pride.

Education is a critical part of my talk and my passion for education is deeply rooted. I’ve enjoyed my role as Governor and my parents were both teachers. From them I learnt a love of learning, respect for hard work, and for educational practitioners. My parents moved from their small flat in Chester, found a town they could afford a mortgage on with two NQT salaries equidistant from the schools they taught in. My brother and I were raised in a new town built following rapid growth of Liverpool and Manchester. It was poorer than surrounding towns but I made good friends and learnt well there. My brother and I both went off to Oxbridge.

Is that a second label I wear? Yes.

Is it all bountiful? No.

Some people associate Oxbridge with hard work and intelligence.

Others discredit it as privilege. As their eyes visibly roll back and their tongue moves to their cheek, they don’t stop to ask if I am.

Their preconceived notions of a privileged background become a barrier to learning what we may have in common, and consequently what we may achieve together.

In response to those people, and in order to avoid the difficult recognition that their perception of me has become a barrier, I could choose to hide this part of my story. Just in case. Keep tight lipped and hold my tongue. Arguably, I could hide many characteristics and experiences to suit other’s narrative. But I choose not to. It’s a choice I’ve had to practice and perfect. I’d rather bring my full self to every interaction but the choice was uncomfortable before it became unapologetic. I realise now, I often witnessed my parents see the same eye roll during our long summer holidays camping. I recognise some have pre-conceived perceptions of life as a teacher too. 13 weeks ‘holiday’ and a 9-3 job, right? (My tongue is firmly in cheek!)

However, labels associated with professions and academic backgrounds aren’t visible. I don’t advocate for it, but the socially constructed labels of ‘otherness’ could be hidden, and the barriers to being viewed beyond these labels can be hurdled, should we choose.

These labels aren’t as clear, for example, as the colour of my skin, the lines on my face. Or my gender.

My experience of gender inequality is multi-faceted. It has been life changing. I am a gang rape survivor.

Three years later I broke. So damaged by that experience I did not know how I could survive. I spent hours contemplating how I would die. But I didn’t. I asked for help.

And I got it. I used my recovery to support others and rewarded with leadership training. I learnt how to be my most authentic self. I became acutely aware of my strengths and passions. Instead of focusing on improving my weakest areas, I learnt to recognise where they correlated with other’s strengths. Together, we would achieve far more together than competing apart. Productivity and wellbeing increased. I love a win:win.

However, men are three times more likely to die by suicide than women – although there is a frightening increase for both genders. Yet I wonder: could men and boys need women’s support as much as I need theirs?

Since my TEDx, I’ve learnt a frightening amount about the challenges men face, in silence. I had anticipated the warmth of my sisters in recognition that I may have found the missing key to inequality. But instead, I have been overwhelmed by the response of men.

Privately, rarely publicly, men have approached me with excruciating trauma stories. Suffering as children or adults to be seen as who they truly are. Men from each continent, age, race and profession are struggling. Unlike women, who are born and raised in a society with equality in mind, our boys and men must – without resources – adapt to a world that is changing.

Education, Equality and Allies: What’s Gender got to do with it?

26/6/2020

By: Hannah Cotton

Originally published: MenTeachPrimary

June 4th 2020

Keynote Speaker and Consultant. @HannahCaC79 #FFBInclusion

My favourite poet is a chap called Brian Bilston. His work is aesthetically and linguistically delicious – words placed on a page with such imagination and creativity, he’s a true inspiration. His infectious delight in word play encouraged me to take it up myself, reminding me how much I used to love my English lessons at school.

One example of my word play builds on equality and the role of allies. My brain child EquALLIES was born following my TEDx, #KillerStereotypes, which outlines why I think we can accelerate equality when we work together as Equal Allies. It hinges on the labels we wear, consciously and subconsciously and how we can use them to promote inclusion at home, school and the community.

Since that talk, some have called me an educator. I know my stuff and share my knowledge and experience to inform and encourage others to think differently. But it’s a label I struggle to associate with. I’m not qualified as a teacher. I’ve not got the skills and experiences you have in drawing out the potential of others. However, if listening to my conversation calls the reader or viewers to consider things differently, ‘educator’ is a label I wear with humility and pride.

Education is a critical part of my talk and my passion for education is deeply rooted. I’ve enjoyed my role as Governor and my parents were both teachers. From them I learnt a love of learning, respect for hard work, and for educational practitioners. My parents moved from their small flat in Chester, found a town they could afford a mortgage on with two NQT salaries equidistant from the schools they taught in. My brother and I were raised in a new town built following rapid growth of Liverpool and Manchester. It was poorer than surrounding towns but I made good friends and learnt well there. My brother and I both went off to Oxbridge.

Is that a second label I wear? Yes.

Is it all bountiful? No.

Some people associate Oxbridge with hard work and intelligence.

Others discredit it as privilege. As their eyes visibly roll back and their tongue moves to their cheek, they don’t stop to ask if I am.

Their preconceived notions of a privileged background become a barrier to learning what we may have in common, and consequently what we may achieve together.

In response to those people, and in order to avoid the difficult recognition that their perception of me has become a barrier, I could choose to hide this part of my story. Just in case. Keep tight lipped and hold my tongue. Arguably, I could hide many characteristics and experiences to suit other’s narrative. But I choose not to. It’s a choice I’ve had to practice and perfect. I’d rather bring my full self to every interaction but the choice was uncomfortable before it became unapologetic. I realise now, I often witnessed my parents see the same eye roll during our long summer holidays camping. I recognise some have pre-conceived perceptions of life as a teacher too. 13 weeks ‘holiday’ and a 9-3 job, right? (My tongue is firmly in cheek!)

However, labels associated with professions and academic backgrounds aren’t visible. I don’t advocate for it, but the socially constructed labels of ‘otherness’ could be hidden, and the barriers to being viewed beyond these labels can be hurdled, should we choose.

These labels aren’t as clear, for example, as the colour of my skin, the lines on my face. Or my gender.

My experience of gender inequality is multi-faceted. It has been life changing. I am a gang rape survivor.

Three years later I broke. So damaged by that experience I did not know how I could survive. I spent hours contemplating how I would die. But I didn’t. I asked for help.

And I got it. I used my recovery to support others and rewarded with leadership training. I learnt how to be my most authentic self. I became acutely aware of my strengths and passions. Instead of focusing on improving my weakest areas, I learnt to recognise where they correlated with other’s strengths. Together, we would achieve far more together than competing apart. Productivity and wellbeing increased. I love a win:win.

However, men are three times more likely to die by suicide than women – although there is a frightening increase for both genders. Yet I wonder: could men and boys need women’s support as much as I need theirs?

Since my TEDx, I’ve learnt a frightening amount about the challenges men face, in silence. I had anticipated the warmth of my sisters in recognition that I may have found the missing key to inequality. But instead, I have been overwhelmed by the response of men.

Privately, rarely publicly, men have approached me with excruciating trauma stories. Suffering as children or adults to be seen as who they truly are. Men from each continent, age, race and profession are struggling. Unlike women, who are born and raised in a society with equality in mind, our boys and men must – without resources – adapt to a world that is changing.

“Every time we acknowledge our daughters have the capability and right to be whatever they want to be; firefighters, fighterpilots and surgeons, let’s ask – why aren’t our sons told they can be nurses, child care providers and secretaries?”

(TEDx, KillerStereotypes)

I argue that for any inequality we face, we must learn to recognise the strengths of the individual and barriers they may experience to achieving all they can be. Equality is only limited by exclusion – in the truest sense of the word. I lend from the work of Daniel Sobel[1] in flagging that as soon as you exclude a child from your setting, be it an intervention for any reason, there is an impact on both the individual excluded and those that remain in the room. Therefore, by automatically perceiving gender as female, we exclude the male. By interpreting race as BAME, we exclude white. We negate the experiences of “otherness”, artificially augmenting the size and volume of our label so the individual beneath becomes lost. I believe that to address inequality we must look beyond the label, learn from successful inclusion programmes and promote change from BOTH sides of the spectrum.

For example, gender inequality in education is abysmal. For women, education has the 5th worst gender pay gap of all sectors in the UK[2]. This is largely due to the small percentage of male teachers entering the profession rising rapidly to the senior leadership roles. And women (rightly) need resources to understand and address the causes for that. As male allies, I’d encourage you to follow the #WomenEd conversation, talk with your colleagues about how you can support them. In the post – #MeToo era, I understand men can feel nervous about having genuine concerns being misinterpreted. There’s too much for this article to teach you, but I’d be happy to help you understand how.

It seems that like in many other industries the gender pay gap for women in education may be linked to returning to work after childbirth. It’s largely accepted that changing the focus of female as lead parent to men and women as equal parents, the uptake of the shared parental leave is still crushingly low. Only 2% of families taking the opportunity. There is a cycle of discontent as families – where the women are often in lower paid jobs – can’t afford to do what’s best for their family.

Equally, I’ve had many a conversation with women that pointedly refuse to share parental leave. “I’ve got the stretch marks and he doesn’t deserve time off”. So, as much as we must include men in our solution to address gender inequality, we can’t exclude women as part of the solution too.

I’d like to see more resources being targeted at the other end of the scale too: where are men and boys over and underrepresented? I’ve already mentioned the scathing inequality in men’s overrepresentation in those who die by suicide, but this majority is also reflected in prison populations, homelessness and drug abuse. It’s not just CEO roles in the FTSE500 where men are the majority.

Let’s look at this another way – instead of seeing this as a male minority, what drives the inequality of the female minority?

What is going well for women, and what can we learn that might support men?

What is going well for men, and what can we learn that might support women?

Little known fact for the staff room – women in prison are in a similar minority as men are in Primary education at 5%. One difference should you find yourselves incarcerated as a parent, is that as men, you’d have less rights. A great amount of work has been undertaken to understand the damage of incarceration on a female parent’s dependent child[3]. The bond a mother has with their child is, it seems, not as important as that of a father. I have a father and so do my children and I’d contest that notion very much. I wonder if the same time and attention was focused on normalising equal roles for male and female parents, we could reduce crime, helping the children, prisoners and communities too?

After all, if “we can’t be what we can’t see”, where are boys getting a diverse set of role models? During Covid, my children’s school asked all the students to send pics of the children’s aspirations. For both Y2 and Y4 over 90% of boys wanted to be footballers, whilst girls demonstrated a great diversity of dreams: Doctors, Scientists, Authors, Singers, Dancers, Teachers, Vets. What messages are our young daughters getting about the wealth of opportunities that are available to them, which our sons are not? I wonder how much that contributes to the struggles young men face as they enter adulthood?

Regardless, we have a recruitment crisis in the UK. Low paid, nurturing professions are in desperate need of professionals. Teaching and nursing and the obvious ones. So, I wonder why there aren’t male-focused recruitment drives? They have had an impact in finance, legal and civil service sectors for women. They may also support any role model issues for children with limited male role models at home.

In a governor’s position I have scrutinised the gender breakdown trying to understand the barriers to entry for men into primary and I wasn’t surprised to hear the following;

- I was the only one at university studying this course.

- My friends said I was crazy to want to.

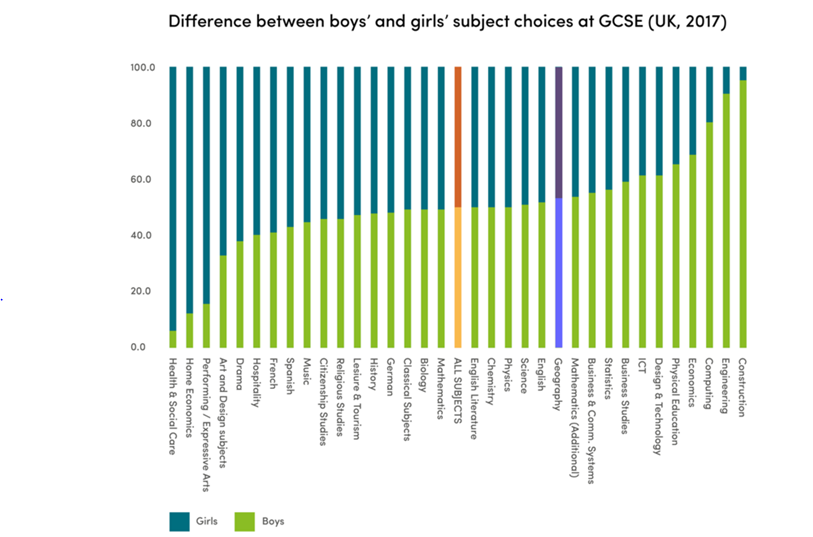

These are both common barriers for women entering STEM careers too. Resources are focused on bringing more diversity to the right hand side of the chart below, but I’d like to know, how are we working with girls, boys and communities to address the left? (Source: Data from the Joint Council for Qualifications, 2017)

But I’ve never heard women in STEM face dangerous association with their career choice linked to criminal behaviour. Two of three male primary teachers of one school telling me:

- Some people say I must be a paedophile

Here, I see us facing a frighteningly deep rooted societal issue. I want to dig further. Who thinks this? Are they fathers? Did they not change their child’s nappy? Are they in positions of responsibility or power? Do they suffer with addiction to substances, gambling or porn? Are they in relationships? Are they violent? Why would they sexualise education? Are they paedophiles? Have they been abused? Are they happy? Do they need help?

Remember, my father was a teacher. So, for women who work with children to be normalised whilst men are confused with having lust for hideous violent crime is deeply disconcerting. Society – men and women – must challenge this narrative promptly to empower and enable men and women to work in any industry as equals.

If not, how do we teach the next generation that there are good men? They certainly aren’t all professional footballers. Even if they are, they are often unhappy and unfulfilled having never realised they could have been a teacher. Or nurse. Or poet. Or dancer. Or vet….

So, as well as applauding your role in demonstrating to young children in your schools that men care, educate and empathise I’d like to say should you need me, I will help you. I hope you would help me too. I see the strengths you bring to the table and the barriers you face. I see that they’re different to mine.

Reassuringly, the commonality of our difference is what makes us equal.

Beyond the labels, to EquALLIES, we are equal allies.

[1]https://www.amazon.co.uk/Narrowing-Attainment-Gap-handbook-schools-ebook/dp/B0725LG82Z

[2]https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-47252848

[3]https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt201719/jtselect/jtrights/1610/full-report.html